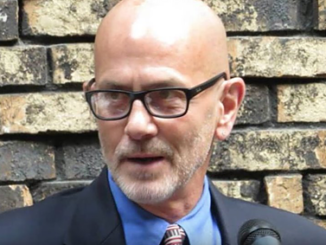

We’ve pointed out on numerous occasions how Bismarck Mayor Mike Seminary shows complete disregard for North Dakota’s Corrupt Practices Law. We discussed some of the more minor infractions back in December. Then in February we were contacted by employees from the City of Bismarck who shared with us how Seminary was inappropriately gathering re-election signatures in the workplace. But perhaps the most damning evidence came earlier this month when we showed that Seminary had literally been filming campaign material on city time and property, where candidates are prohibited from doing so.

One Bismarck resident recently filed a complaint with the Bismarck Police Department against the mayor for Corrupt Practices. The complaint was then sent on to the Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI). And this morning we weren’t surprised at all to find out that BCI reported back to the complainant that they had conveniently found no wrongdoing.

I’ve now had the opportunity to review documentation, obtained through an open records request earlier today, that shows BCI’s search for the facts to be less than stellar. To put this into context, BCI sought out the opinion of Jonathan Byers and Britta Demello Rice, who both work in the Attorney General’s office. In an e-mail from Byers to BCI Director Dallas Carlson, he says:

“Britta and I reviewed the videos, and it appears to be the mayor going about his daily duties. The statute specifically states that ‘political purpose’ does not include activities undertaken in the performance of public office.” (Emphasis in the original.)

In an earlier e-mail from Director Carlson to BCI Chief Agents Lonnie Grabowska and Phil Pfennig, he says:

“I talked with Byers and Britta. Both said no crime was committed. The only way it would be a crime is if he made the video and photos specifically for his campaign. Using stock footage is not a crime. Tim will talk to the PD and let them know.”

But here’s the problem… What effort was made on the part of BCI to determine which video footage was “stock” and which wasn’t? Prior to BCI’s decision to deny the “request for an investigation”, there was an open records request made with the City of Bismarck to obtain all footage from the events shown in Seminary’s campaign videos. But get this… NONE of the footage provided by the City of Bismarck is in his campaign videos. Which means that EVERYTHING he shot was for campaign purposes. By Carlson’s own admission, this “would be a crime”.

Furthermore, there appears to have been absolutely no effort on the part of BCI to determine who shot the video footage that Seminary used. The Corrupt Practices Law is clear that the definition of “Services”:

“… includes the use of employees during regular working hours for which such employees have not taken annual or sick leave or other compensatory leave.”

So, who shot the video footage? And why didn’t BCI look for answers to that question? If it wasn’t a city employee doing the videoing, are we then saying it’s okay for Seminary to bring campaign staff in to shoot the footage? How would that too not be a violation of the law? And what about his selfies? Isn’t he an employee of the city? Why isn’t it a violation for him to shoot his own campaign videos on city time and property?

Perhaps the most glaring oversight by BCI is in relation to Seminary’s collecting re-election signatures on city property during regular business hours. As we mentioned earlier, we wrote about that situation back in February when we were contacted by employees from the City of Bismarck regarding the issue. Yet, the information obtained in the open records request shows absolutely no mention of it at all. Why wasn’t this addressed by BCI? It’s a blatant violation.

The fact that BCI claims no wrongdoing on the part of Seminary also shows a double standard. I wrote back in March about a case in Western North Dakota in which Alexander City Councilman Jerry Hatter was forced out of office for his violation of the Corrupt Practices Law. How so? While participating in the city’s Old Settlers Days Parade last September, Hatter hung a bedsheet from a fire truck, with the words “Vote for Hatter” painted on it.

The decision to hang the bedsheet on the fire truck was not only questioned, but ultimately BCI looked into the matter and charged him with a Class A misdemeanor for using state services or property for political purposes. Initially, Hatter entered a plea of not guilty, but McKenzie County State’s Attorney Chas Neff offered to drop the case if Hatter would resign his position– which he did.

This leads me to wonder… How can Hatter’s actions be a violation, according to BCI, and Seminary’s not? On the one hand, we have a bedsheet hung from a fire truck with the words “Vote for Hatter” painted on it. On the other, we have Seminary literally being filmed on city time and property for campaign videos that say, “Re-elect Seminary for Mayor”.

At best, this was shoddy work by the Attorney General’s office and BCI. If we’re going to accept that a mayor can make campaign videos on city time and property, under the guise of “activities undertaken in the performance of public office”, then why in the heck do we even bother having a Corrupt Practices Law in the first place?

The Attorney General’s office and BCI completely overlooked important facts in the case and in the process they turned a blind eye to Mike Seminary’s violations of the Corrupt Practices Law.

Sources:

- http://www.legis.nd.gov/cencode/t16-1c10.pdf

- https://theminutemanblog.com/2017/12/07/city-of-bismarck-mike-seminary-corrupt-practices-and-stifling-dissent/

- https://theminutemanblog.com/2018/02/12/did-bismarcks-mayor-mike-seminary-inappropriately-gather-re-election-signatures/

- https://theminutemanblog.com/2018/05/15/bismarck-mayor-campaigns-taxpayer-dime/

- https://www.ndcourts.gov/court/lawyers/06867.htm

- https://www.ndcourts.gov/court/lawyers/06867.htm

- https://theminutemanblog.com/2018/02/12/did-bismarcks-mayor-mike-seminary-inappropriately-gather-re-election-signatures/

- https://theminutemanblog.com/2018/03/19/bci-investigates-mckenzie-county-settles-corrupt-practices-case/